FORCES EVOLVE FORM

“When I’m working on a problem, I never think about beauty. I think only how to solve the problem. But when I have finished, if the solution is not beautiful, I know it is wrong.”

- R. Buckminster Fuller

According to Keats, ‘truth is beauty, beauty truth.’ It follows that designs that emerge from truth are inherently beautiful. This kind of beauty does not rest on the visual surface of the object alone, but rather comes alive through the mediation of multisensory perception.

PARABOLA posits an approach to architecture that seeks such a self-evident and universal beauty by studying these ethereal elements and embracing their capacities to derive experiential form.

Light, air, sound, touch, thermodynamics, perspectives, time—architecture is in constant dialogue with natural forces that extend far beyond what we can see.

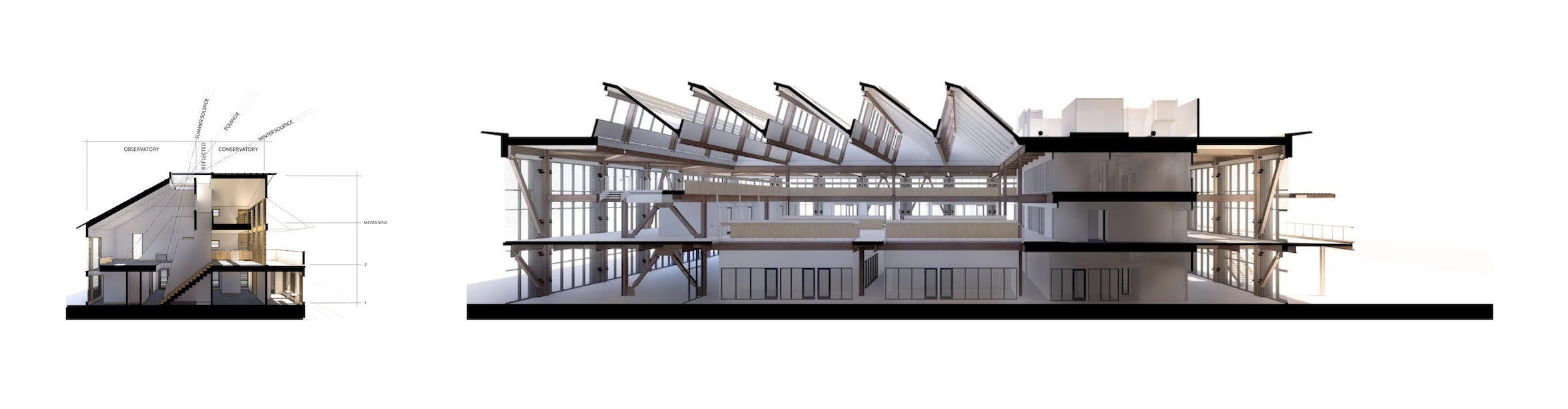

Oriented true solar north/south, the north roof form of Timepiece maps the parabolic path of the sun at the winter solstice. This form did not result from an effort to design a beautiful roof, yet it is observably beautiful. The observer’s response to this form appears rooted in a deeper aesthetic realm that transcends individual stylistic preferences.

Designs that evolve from natural forces resonate with our senses and our humanity. In this process, beauty is the gauge, not the goal.

PARABOLA posits an approach to architecture that seeks such a self-evident and universal beauty by studying these ethereal elements and embracing their capacities to derive experiential form.

Light, air, sound, touch, thermodynamics, perspectives, time—architecture is in constant dialogue with natural forces that extend far beyond what we can see.

Oriented true solar north/south, the north roof form of Timepiece maps the parabolic path of the sun at the winter solstice. This form did not result from an effort to design a beautiful roof, yet it is observably beautiful. The observer’s response to this form appears rooted in a deeper aesthetic realm that transcends individual stylistic preferences.

Designs that evolve from natural forces resonate with our senses and our humanity. In this process, beauty is the gauge, not the goal.

A CONVERSATION WITH KEVIN BURKE

PARABOLA Architecture principal Kevin Burke sat down with his daughter Ava to reflect on his path to architecture, pivotal moments in his career, and the legacy and future of the sustainable design movement.

Ava Burke:

You had an unconventional journey towards architecture. Can you talk a little bit about that journey?

Kevin Burke:

I think I found myself always being interested in both architecture and—I don’t know if there’s even a discipline associated with it, but the nature of place.

Growing up where I did, at Fort Lewis in Washington—that base had such a connection to the natural environment. We lived across from the parade ground, and at one axis of the parade ground was Mount Rainier. It was just such a powerful element in my mental landscape. That combination of architecture and place, or architecture and the environment, really had a big impact on me.

So I think I was always pretty eyes wide open to the physical environment. And in school I was always interested in history and art, but I didn’t really know what avenue would combine all of those interests. I just found myself gravitating to those realms, and thankfully discovered architecture as the way to channel all those diverse interests.

I got my undergraduate degree at Stanford studying International Relations; it was kind of a catch-all as part of a broad liberal arts education. Within that discipline I was really drawn to history and modernism, and was able to take some really good courses in those subjects.

I combined that with studying for a quarter overseas in Tours, France. Although I wasn’t particularly on an architectural curriculum, I spent all my time when I had weekends to travel and hitchhike through Europe visiting cities and exploring architecture on my own—both historical examples and modern buildings. I was almost doing it without knowing where it might lead, but just following my deepest interests.

AB:

And you went to UVA not having any prior background in architecture. What was it like entering that graduate experience?

KB:

It was incredibly challenging, but there were also times where I would pinch myself and think, wow I can’t believe I get to study this. I could spend all of my time thinking about these things that were of great interest to me. And being in a setting like UVA was quite powerful, I think, as a place to absorb architecture at scale.

AB:

You studied abroad in Venice when you were at UVA, with mom [Carrie Meinberg Burke] joining you there. How do you compare those two times in Europe, before and after beginning to study architecture?

KB:

It’s interesting because I get this feeling every time I go to Europe, that you pick right up where you left off, even if it’s ten years later. So in some ways I saw it as a continuity of my personal interests, but I was developing this lens—having studied architecture for a couple of years—I was beginning to understand the discipline.

And I think the chance to get that full immersion in Venice probably was the turning point of my graduate education. It was like crossing the threshold as a young architect, because it combined so much at a time when I was ready to receive its instructions.

I don’t think I’ve ever sketched as well as I did at that time, because it was just part of everyday experience. And our classes were often just in the city itself—art history, architectural history, the design studios, all of those were basically using Venice as the classroom. It was extraordinary.

AB:

And then you started working in DC and then in New Haven for César Pelli, and then found your way to William McDonough + Partners, where you spent a long time and became a partner. That transition to a focus on sustainability and integrated design—I want to hear about how that became a central part of your practice.

KB:

Coming out of even a three-year grad program, you still feel the sense of needing to catch up. I was really fortunate because the office I worked in—and met Carrie in—Oldham and Seltz, was a spin-off of Skidmore, Owings + Merrill’s DC office. It was a really great place to learn the discipline of architecture and how to actually practice architecture: how to put buildings together, how to draw and detail and delineate design.

After that, when Carrie went to graduate school at Yale, I got a position with César Pelli’s office, and that was an immersion in a world-class design studio. The longer I was there, I understood the lineage César had from working in Saarinen’s office, project teams that he was a part of—TWA, Dulles—and the focus on model-making and iterative explorations through physical models. It was a really great way to round out my design education.

Even where the office was located was an inspiration. It’s right across from the Yale campus, across the street from two Lou Kahn buildings: the British Architecture Center and the Yale Art Museum, and then another block away from the Yale School of Architecture. So in this little two-block radius was an incredible amount of inspiration, and for Carrie and I, just a deep dive in architecture. That was right before you were born.

I feel really fortunate for the chance to work with César, and to see how César worked with his partner, Fred Clark, and to be in a culture and on teams with an incredible array of talented architects, many of whom have gone on to start their own practices and be quite successful. It felt like a chance to be part of a lineage and legacy.

AB:

And then you joined William McDonough + Partners, in 1994. I know we’ve talked a lot in offline conversations about what that era was like as a coalescing for sustainable architecture, and an emergence of a whole new generation of thought around that.

I’m curious about your take on that now, thinking about where the sustainability movement has gone from that point. What did it feel like to be involved in that in the early stages?

KB:

It is really interesting to look back on that time, because despite how successful and well-rounded the practice was at Pelli’s, sustainability wasn’t one of the concerns. And that’s not a knock on César’s practice—within the profession, very few architects were even engaging in what has now become sustainability.

It was a time, though, when Carrie was doing these explorations at Yale, particularly around light as a form generator and explorations in daylight. And there were these discussions that we had about finding a way to design and build our own house—based on the things I was learning practicing at Pelli’s and what Carrie was learning at school—what would this mean for us?

There was a moment when we were exploring where we wanted to live and also how we wanted to practice. We had even put together a curriculum for a seminar course at Yale on daylight and lighting, and that was kind of our first time thinking about our combined approach to architecture, and in some ways it was the seed of our consideration beyond just formal design—the more experiential or ethereal elements that inform architecture or the experience of architecture. These were the things that were brewing as I learned about the opportunity to work with Bill McDonough.

He had been named dean of the architecture school at UVA, and it turns out that a couple of former Pelli colleagues—Chris Hayes and Allison Ewing—were working with Bill at his practice in New York City.

I called Chris up and asked if they were planning to move the practice to Charlottesville, what were they working on, and were they hiring? And he said, in fact, that they were going to relocate to Charlottesville, and that they had just won a competition in San Francisco for the Gap company. They were going to be working on a new corporate building for them.

One thing led to another and the next thing I knew, Carrie and I—and you, Ava—were on a train to New York City and we met Bill for the first time and I interviewed at his office in midtown and was offered a job, basically.

The people in Bill’s office who were the old-timers, none of them had decided to move to Charlottesville. So besides Chris and Allison, Bill was looking to form a whole new office. And in some ways, it was really a great opportunity as a fresh start with a whole new team.

It turned out that there were a number of people from Pelli’s influence—and even the Saarinen lineage—that made their way down to Charlottesville in the early days of William McDonough + Partners. It was a great way to have a shared language and shared processes merge with this entirely new way of thinking about architecture around sustainability. It was a really exciting time.

AB:

And then you started working on the Gap project. I remember visiting that project as a child when it was under construction, and I remember you putting me up onto the green roof and thinking it was so cool.

What was it like to work on that project in particular? Especially since it’s having a renaissance now, with a second phase being developed almost 30 years later?

KB:

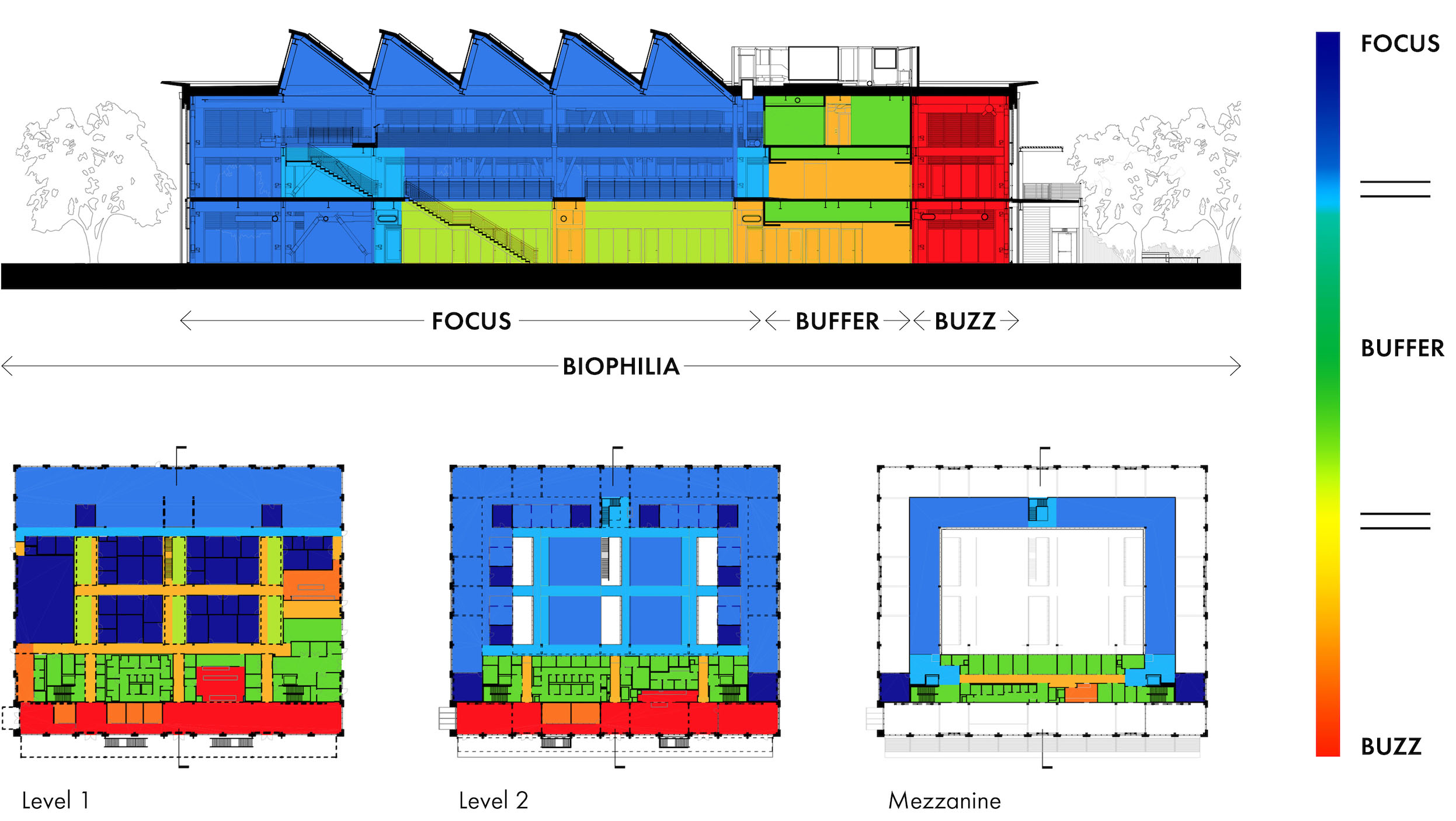

McDonough’s had won a competition at the Gap, and had competed against firms like HOK and Gensler. It was Bob Fisher, son of Don Fisher, founder of the Gap, who really had a strong interest in sustainability. And I think the charge for the design competition was maybe not explicitly saying sustainability, but they were looking to explore new ways of thinking about corporate office space with a greater connection to nature.

Chris Hayes was the design principal and Chris and Allison had done the competition, working closely with Bill. What was fascinating was that I kind of inherited what, looking back on it now, was a very simple document—just an 11x17” xeroxed copy of their competition entry, which had some of the elements you mentioned, like the grass roof.

The document also showed a form that allowed daylight to be generated at high points and bounced through the space. It had a suggestion of an under-floor system for air delivery that would get air to people’s breathing zones. It described operable windows—which was unheard of at the time. It was a combination of elements that were definitely new and distinctive in the States, but had been tested in Europe and were emerging.

Gap paired us with Gensler as the executive architects, so there was this energy of us as a little seven-person office teaming with one of the biggest offices in the world, and it felt like everyone was wondering whether this small, emerging firm could actually succeed in pulling this off.

But we did, and there was a spirit on the team that we were really doing something different. We worked with Arup on structural and mechanical, with Hargraves on the landscape, and Paul Kephart on the grass roof and native grasses. It was an early instance of just realizing the importance of getting people on the delivery side on board with the execution of the project, and that it really comes from them understanding why things are the way they are [in the design].

It had a quality that is akin to the spirit Carrie and I had, on a much smaller scale, in building our house.

AB:

And those two projects were in fact happening at the same time.

KB:

You’re right, the Gap project was happening when we had bought the land and were thinking about the design for our house.

AB:

And then you went on to work on a really special building at Oberlin that is still seen as a big waypoint in the history of sustainable architecture. Can you talk a bit about your relationship to David Orr and how that came to happen?

KB:

We had just finished the design of the Gap and were starting construction in 1996, and at that time Oberlin College had issued an RFP for this environmental studies center, which was for David’s new interdisciplinary program at the school.

McDonough’s office ended up being selected to be the lead designer for the project. This felt like another step up in terms of the level of ambition sustainability-wise, and looking back on it, I feel like Oberlin was kind of a postgraduate education.

David had raised the bar to a level that I think became the seed crystal for the Living Building Challenge and the Living Building Institute—the way the performance aspects and the ambition of the project was defined was really groundbreaking, I think. David had put that together with the early luminaries of the sustainability movement—Bill McDonough, Amory Lovens, John Todd, Paul Hawkins—he had the who’s who in this emergent realm of sustainability.

What struck me was how David had worked with students over the course of a few semesters, in workshops and charettes, to define the program and the principles for the project. And they were advised by the advisory group, but the full ambitions of the project emerged from this deep engagement by the students, which was in some ways the fractal of the entire project. It was David’s goal for the building to be a pedagogical tool, so it was really fitting that it would emerge from this engagement with faculty and students.

What I recall was the elegance of the project program and the way that the RFP was stated. It was really inspiring, and it set the bar for how sustainable ambitions can be voiced.

Instead of being prescriptive, it just asked a series of questions: How can we design and operate building on current solar income in northern Ohio? How can it create more energy than it uses over the course of a year? How can we create no ugliness upstream or downstream in the making of this building? How can the building process and reuse its own waste by functioning as a living machine? How can the landscape be both instructive about ecological processes, but also informative to the students about where they are on the planet?

To me, voicing those questions was very powerful.

And it was a reminder, looking back on it, of how challenging it is to actually meet those objectives. We had WM+P’s sister company, MBDC, on our side, and access to some incredible indoor air quality experts, but it was hard to try to assess every material selection on the project, and every specification, when there just wasn’t deep research on much of anything. There were no product lists we could go to to meet those specifications. It was a steep learning curve.

AB:

In the era of LEED and Living Building Challenge and the codification of sustainability in architecture, how does it feel to look back on the Oberlin building as a progenitor of that?

KB:

I think David saw the building as a stepping stone, and it was interesting working with him closely throughout that whole process, because he was a great leader. He both saw the critical importance of getting the building right, but he always had a view beyond it at the same time. It was a unique quality, I think, to be in the midst of something that intense and be able to step back and see the long game.

What he realized, I think, was that if they get this building built, it will become a seed crystal. It will be an attractor for students and faculty, it will put the college on the map and maintain the progressive legacy that Oberlin’s had throughout the years. It was the next step in that lineage.

But he had a vision of a campus-wide sustainability initiative back in 1998, which they were calling the 2020 Initiative—which is ironic, being now past 2020—where they were looking at carbon emissions and getting a zero-carbon campus. What would it take to achieve that, having just gotten to a net-zero, net-positive building?

Also what was special with David and his view of sustainability was that the vision didn’t stop at the confines of the campus. Oberlin is such a great example of the small liberal arts college in a small town, and the melding of campus and community.

It has quite a beautiful layout of a central green, with the college on three sides of it and the town on the fourth side. But the town was facing a lot of economic hardship. So David saw this initiative of sustainability operating at the scale of the college, the town, and the region, and integrating all of those together. He would use the building project as a means of engaging city leadership and community residents in the nature of the project, and expanding the aspirations of the project to become more of a regional initiative.

A number of the recent graduates from David’s program became restauranteurs in town and established restaurants based on local [food] production; they became developers and developed LEED-certified buildings downtown and helped revitalize the downtown; they started a farm that Oberlin owned that was growing local food and was supportive of food production in the community; they started to influence the curriculum in local schools.

So I think the seed crystal quality of the project, and the nested scales of ambition that it was able to address, is still unique and is a great model, even in this era. So many projects have looked to build upon Oberlin and exceed its achievements, which is the whole point.

AB:

I want to hear a little bit more broadly about how codified sustainability has become in the realm of architecture. What are the opportunities and limitations?

KB:

That’s a good question. So the Gap was from ‘94, built in ‘97; Oberlin started in ‘96 and took until 2000 to finally be built. The US Green Building Council was emerging in the late ‘90s and the first USGBC conferences were happening in 2001, and LEED 1.0 was right around then. The Committee on the Environment—the AIA’s group—was forming in the early ‘90s and was just starting to hit stride in the early 2000s. So I think the entire movement started to come to light in the late ‘90s. Architectural practices and even owners were starting to take stock of the movement in the early 2000s.

LEED was really critical to the rapid growth of the movement, I think, because it gave a framework that design teams and engineers could all refer to. But just as importantly, it was for owners and builders to have a checklist, and a reference point for what success might look like.

To LEED’s credit, they continued to evolve the certification and the standards to incorporate new input. I think the evolution of LEED over time has been positive, in that it has increasingly taken into account local conditions, local markets, and health and well-being. All of those things are positive.

I remember going to some of the US Green Building conferences in that era where people were also trying to crack the code on the economics of green buildings. Major developers like Hines were seeing the corporate interest and the ‘good design is good business’ side of things, but they were trying to get the economics down, especially when you were incorporating so many new systems that hadn’t been incorporated in buildings at scale before.

It was a reminder of how extremely challenging buildings are in the first place. And then throw on top of that this high bar agenda that has to succeed on environmental issues, health issues, economic issues, and the equity and social component of sustainability as well.

Even looking back on this 25-year, 30-year arc and the great successes and the incredible work people have done, we’re still in very early days in terms of really, as a culture, achieving sustainability. It’s still kind of this goal to pursue.

And the greatest challenge now is the realization that we just don’t have that much time, with the imperatives around climate change and carbon. It’s almost like the realities are kind of coming into focus as our skill-set is emerging, and I think it’s a real question whether we’re going to be able to get there in time.

AB:

Can you talk about the experience of working with Bill McDonough in particular? How was the culture of his office distinct?

KB:

I feel fortunate to have had the chance to work so closely with Bill over the course of 16 years, at a time when the movement was so emergent and he was playing such a pivotal role in that.

What stands out in my memories of William McDonough + Partners is that there was always a need to do what architects do within practice—all of the opportunities and challenges that come along with just doing projects—but there was always something more that was associated with what Bill was doing and trying to achieve in the world. So we had to navigate both realms concurrently.

We had great opportunities with companies like the Gap, or Ford, or Aspect Communications, VMWare, or communities, cities, or regions that would be interested in the way of thinking. There was always the design task at hand, but we were also trying to forward a movement, whether that was Cradle to Cradle or sustainability writ large. And that could be, at times, quite frustrating and quite challenging, but it was what kept it exciting and a unique way of thinking about the role of design.

AB:

You mentioned communities—one of the other projects I wanted to ask you about was the Fuller Chapel, which was one of the other projects you designed while at McDonough’s.

From what you’ve told me, that space was designed to serve a lot of different functions for different communities, and feels like a very community-informed design. What was your experience with that?

KB:

Fuller, in some ways, is emblematic of the type of projects we would get at McDonough’s, and the levels of engagement that would come with that. We got the project initially because one of the board members at Fuller, William Brehm, had come across Bill in their mutual work with Herman Miller. He was taken by Bill’s thinking and approach to sustainability and its potential to impact the entire Fuller community—which is one of the largest, if not the largest, interdenominational theological seminaries in the country.

We were involved for many years, first doing master planning for the campus and then getting the opportunity to design a worship center for them, as well as an addition to their library. It was emblematic of what the seminary was about, which was the head and the heart: the potential for deep research, but also worship.

The unique thing about Fuller is that, although they had been a seminary for 50 or 60 years, they had never had their own place of worship. This became the opportunity to give physical embodiment to this rich, diverse, and creative community. That’s what the worship center needed to embody.

A lot of the worship that happens at Fuller is through performing arts. So in a lot of ways, designing the worship center was like designing a performing arts center. Bill Brehm, in addition to being head of a couple different companies and a philanthropist, is also a composer. So he had a strong desire to see the performance aspects be carried out at the highest level of excellence, and that’s what the design gave us the opportunity to explore and to implement on the campus.

AB:

What elements of that design feel most successful to you, not just in accomplishing what it needed to purpose-wise—and I know there were a lot of complex considerations of different performance configurations and different acoustics—but also on a more ethereal level?

KB:

Unfortunately the worship center has never been built. They did build the addition to the library, but I still have my fingers crossed that someday they will build this. That said, the design was very well-received by the community.

I remember sitting through visioning sessions with the various faculty members and one of the faculty members said, ‘I think this building needs to be a building that can house our dreams as a community.’

There’s something about the way she expressed that—both the poetics of that and the nature of that ambition—that stayed in the back of my mind during the design. This needed to be more than, as you noted, just a lot of high performance around acoustics or flexibility or daylighting.

I do think the design was able to capture a type of spirit in the quality of light and the variable acoustics. They wanted a space that could feel intimate if a single person went in looking for a place of solitude or prayer; if two people were there; if a small quartet were there performing; if it was more of a music group—be it rock music, a capella, or an orchestra. It needed to have a variable acoustic that would make all of those achieve a level of transcendence. And I think the design was able to achieve that.

AB:

Was that one of the first projects where you were dealing with acoustics more centrally, or has that always been a consideration?

KB:

We had addressed acoustics more broadly in corporate office buildings, which was about creating absorption in the space through acoustic metal deck or those types of considerations, or dealing with the sound of an adjacent road or something like that. So it had definitely played a part in thinking about holistic, experiential design, but this was the chance to take it to another level.

We worked with theatrical consultants on how to achieve a variable acoustic, which we developed behind these wooden slat walls that had an absorptive fabric behind them that you could lift or settle depending on how much absorption you wanted the room to have—either to create a very lively, bouncy space or a very absorbent space. You could set that both in the walls and in other acoustic material that could be pulled above a suspended skrim in the ceiling. There was an ability to modulate the reflectivity or absorption of the space that was something more akin to what you would see in an auditorium or performance hall.

AB:

I feel like that high level of consideration in variability of experience feels emblematic of a lot of the other work you’ve gone on to do—your building for Google at 1212 Bordeaux has that quality.

Back to what you had said about the Gap, with the operable windows being against conventional wisdom, the idea of experiential variability feels like a throughway in how you think about design.

KB:

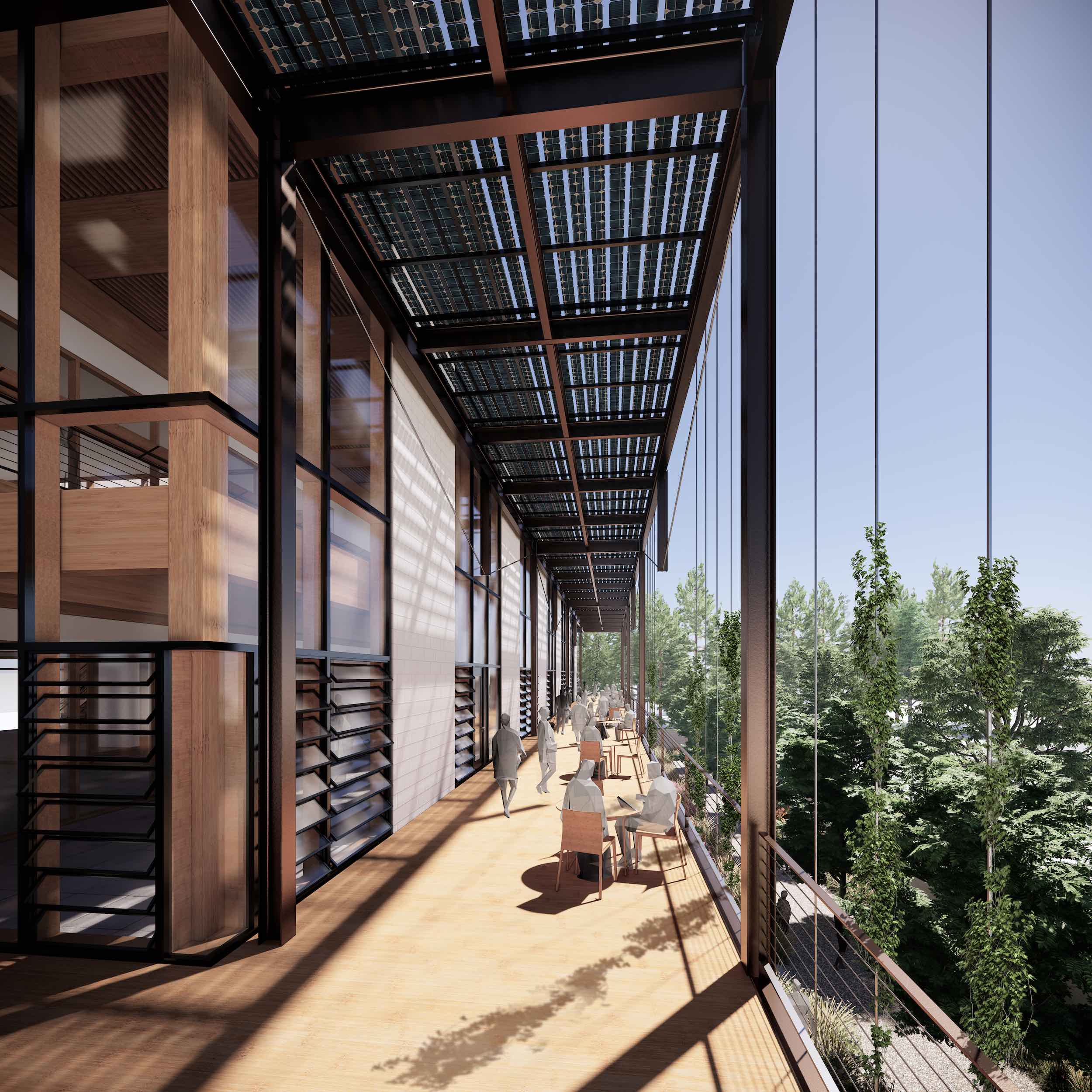

Definitely. In some ways that’s a quality that is part of every project we’ve done, regardless of scale. And actually, in terms of instilling a response—of people feeling really connected to a place—giving options is almost like designing for a cat: you want to create places of thermal variability or light variability that just give people choices.

Prior to this kind of thinking about design, architects had always assumed that a house would give you that kind of choice, whereas an office building had, in the modernist language, been designed to create sameness: the same levels of light, same temperature, same acoustics.

I think a lot of what emerged was from work that Google had done early on, thinking about the office and creating variability as part of it, both inside and outside, and thinking about how the landscape could become part of the office experience. It’s definitely something we have looked to further in all of our projects.

Ava Burke:

You had an unconventional journey towards architecture. Can you talk a little bit about that journey?

Kevin Burke:

I think I found myself always being interested in both architecture and—I don’t know if there’s even a discipline associated with it, but the nature of place.

Growing up where I did, at Fort Lewis in Washington—that base had such a connection to the natural environment. We lived across from the parade ground, and at one axis of the parade ground was Mount Rainier. It was just such a powerful element in my mental landscape. That combination of architecture and place, or architecture and the environment, really had a big impact on me.

So I think I was always pretty eyes wide open to the physical environment. And in school I was always interested in history and art, but I didn’t really know what avenue would combine all of those interests. I just found myself gravitating to those realms, and thankfully discovered architecture as the way to channel all those diverse interests.

I got my undergraduate degree at Stanford studying International Relations; it was kind of a catch-all as part of a broad liberal arts education. Within that discipline I was really drawn to history and modernism, and was able to take some really good courses in those subjects.

I combined that with studying for a quarter overseas in Tours, France. Although I wasn’t particularly on an architectural curriculum, I spent all my time when I had weekends to travel and hitchhike through Europe visiting cities and exploring architecture on my own—both historical examples and modern buildings. I was almost doing it without knowing where it might lead, but just following my deepest interests.

AB:

And you went to UVA not having any prior background in architecture. What was it like entering that graduate experience?

KB:

It was incredibly challenging, but there were also times where I would pinch myself and think, wow I can’t believe I get to study this. I could spend all of my time thinking about these things that were of great interest to me. And being in a setting like UVA was quite powerful, I think, as a place to absorb architecture at scale.

AB:

You studied abroad in Venice when you were at UVA, with mom [Carrie Meinberg Burke] joining you there. How do you compare those two times in Europe, before and after beginning to study architecture?

KB:

It’s interesting because I get this feeling every time I go to Europe, that you pick right up where you left off, even if it’s ten years later. So in some ways I saw it as a continuity of my personal interests, but I was developing this lens—having studied architecture for a couple of years—I was beginning to understand the discipline.

And I think the chance to get that full immersion in Venice probably was the turning point of my graduate education. It was like crossing the threshold as a young architect, because it combined so much at a time when I was ready to receive its instructions.

I don’t think I’ve ever sketched as well as I did at that time, because it was just part of everyday experience. And our classes were often just in the city itself—art history, architectural history, the design studios, all of those were basically using Venice as the classroom. It was extraordinary.

AB:

And then you started working in DC and then in New Haven for César Pelli, and then found your way to William McDonough + Partners, where you spent a long time and became a partner. That transition to a focus on sustainability and integrated design—I want to hear about how that became a central part of your practice.

KB:

Coming out of even a three-year grad program, you still feel the sense of needing to catch up. I was really fortunate because the office I worked in—and met Carrie in—Oldham and Seltz, was a spin-off of Skidmore, Owings + Merrill’s DC office. It was a really great place to learn the discipline of architecture and how to actually practice architecture: how to put buildings together, how to draw and detail and delineate design.

After that, when Carrie went to graduate school at Yale, I got a position with César Pelli’s office, and that was an immersion in a world-class design studio. The longer I was there, I understood the lineage César had from working in Saarinen’s office, project teams that he was a part of—TWA, Dulles—and the focus on model-making and iterative explorations through physical models. It was a really great way to round out my design education.

Even where the office was located was an inspiration. It’s right across from the Yale campus, across the street from two Lou Kahn buildings: the British Architecture Center and the Yale Art Museum, and then another block away from the Yale School of Architecture. So in this little two-block radius was an incredible amount of inspiration, and for Carrie and I, just a deep dive in architecture. That was right before you were born.

I feel really fortunate for the chance to work with César, and to see how César worked with his partner, Fred Clark, and to be in a culture and on teams with an incredible array of talented architects, many of whom have gone on to start their own practices and be quite successful. It felt like a chance to be part of a lineage and legacy.

AB:

And then you joined William McDonough + Partners, in 1994. I know we’ve talked a lot in offline conversations about what that era was like as a coalescing for sustainable architecture, and an emergence of a whole new generation of thought around that.

I’m curious about your take on that now, thinking about where the sustainability movement has gone from that point. What did it feel like to be involved in that in the early stages?

KB:

It is really interesting to look back on that time, because despite how successful and well-rounded the practice was at Pelli’s, sustainability wasn’t one of the concerns. And that’s not a knock on César’s practice—within the profession, very few architects were even engaging in what has now become sustainability.

It was a time, though, when Carrie was doing these explorations at Yale, particularly around light as a form generator and explorations in daylight. And there were these discussions that we had about finding a way to design and build our own house—based on the things I was learning practicing at Pelli’s and what Carrie was learning at school—what would this mean for us?

There was a moment when we were exploring where we wanted to live and also how we wanted to practice. We had even put together a curriculum for a seminar course at Yale on daylight and lighting, and that was kind of our first time thinking about our combined approach to architecture, and in some ways it was the seed of our consideration beyond just formal design—the more experiential or ethereal elements that inform architecture or the experience of architecture. These were the things that were brewing as I learned about the opportunity to work with Bill McDonough.

He had been named dean of the architecture school at UVA, and it turns out that a couple of former Pelli colleagues—Chris Hayes and Allison Ewing—were working with Bill at his practice in New York City.

I called Chris up and asked if they were planning to move the practice to Charlottesville, what were they working on, and were they hiring? And he said, in fact, that they were going to relocate to Charlottesville, and that they had just won a competition in San Francisco for the Gap company. They were going to be working on a new corporate building for them.

One thing led to another and the next thing I knew, Carrie and I—and you, Ava—were on a train to New York City and we met Bill for the first time and I interviewed at his office in midtown and was offered a job, basically.

The people in Bill’s office who were the old-timers, none of them had decided to move to Charlottesville. So besides Chris and Allison, Bill was looking to form a whole new office. And in some ways, it was really a great opportunity as a fresh start with a whole new team.

It turned out that there were a number of people from Pelli’s influence—and even the Saarinen lineage—that made their way down to Charlottesville in the early days of William McDonough + Partners. It was a great way to have a shared language and shared processes merge with this entirely new way of thinking about architecture around sustainability. It was a really exciting time.

AB:

And then you started working on the Gap project. I remember visiting that project as a child when it was under construction, and I remember you putting me up onto the green roof and thinking it was so cool.

What was it like to work on that project in particular? Especially since it’s having a renaissance now, with a second phase being developed almost 30 years later?

KB:

McDonough’s had won a competition at the Gap, and had competed against firms like HOK and Gensler. It was Bob Fisher, son of Don Fisher, founder of the Gap, who really had a strong interest in sustainability. And I think the charge for the design competition was maybe not explicitly saying sustainability, but they were looking to explore new ways of thinking about corporate office space with a greater connection to nature.

Chris Hayes was the design principal and Chris and Allison had done the competition, working closely with Bill. What was fascinating was that I kind of inherited what, looking back on it now, was a very simple document—just an 11x17” xeroxed copy of their competition entry, which had some of the elements you mentioned, like the grass roof.

The document also showed a form that allowed daylight to be generated at high points and bounced through the space. It had a suggestion of an under-floor system for air delivery that would get air to people’s breathing zones. It described operable windows—which was unheard of at the time. It was a combination of elements that were definitely new and distinctive in the States, but had been tested in Europe and were emerging.

Gap paired us with Gensler as the executive architects, so there was this energy of us as a little seven-person office teaming with one of the biggest offices in the world, and it felt like everyone was wondering whether this small, emerging firm could actually succeed in pulling this off.

But we did, and there was a spirit on the team that we were really doing something different. We worked with Arup on structural and mechanical, with Hargraves on the landscape, and Paul Kephart on the grass roof and native grasses. It was an early instance of just realizing the importance of getting people on the delivery side on board with the execution of the project, and that it really comes from them understanding why things are the way they are [in the design].

It had a quality that is akin to the spirit Carrie and I had, on a much smaller scale, in building our house.

AB:

And those two projects were in fact happening at the same time.

KB:

You’re right, the Gap project was happening when we had bought the land and were thinking about the design for our house.

AB:

And then you went on to work on a really special building at Oberlin that is still seen as a big waypoint in the history of sustainable architecture. Can you talk a bit about your relationship to David Orr and how that came to happen?

KB:

We had just finished the design of the Gap and were starting construction in 1996, and at that time Oberlin College had issued an RFP for this environmental studies center, which was for David’s new interdisciplinary program at the school.

McDonough’s office ended up being selected to be the lead designer for the project. This felt like another step up in terms of the level of ambition sustainability-wise, and looking back on it, I feel like Oberlin was kind of a postgraduate education.

David had raised the bar to a level that I think became the seed crystal for the Living Building Challenge and the Living Building Institute—the way the performance aspects and the ambition of the project was defined was really groundbreaking, I think. David had put that together with the early luminaries of the sustainability movement—Bill McDonough, Amory Lovens, John Todd, Paul Hawkins—he had the who’s who in this emergent realm of sustainability.

What struck me was how David had worked with students over the course of a few semesters, in workshops and charettes, to define the program and the principles for the project. And they were advised by the advisory group, but the full ambitions of the project emerged from this deep engagement by the students, which was in some ways the fractal of the entire project. It was David’s goal for the building to be a pedagogical tool, so it was really fitting that it would emerge from this engagement with faculty and students.

What I recall was the elegance of the project program and the way that the RFP was stated. It was really inspiring, and it set the bar for how sustainable ambitions can be voiced.

Instead of being prescriptive, it just asked a series of questions: How can we design and operate building on current solar income in northern Ohio? How can it create more energy than it uses over the course of a year? How can we create no ugliness upstream or downstream in the making of this building? How can the building process and reuse its own waste by functioning as a living machine? How can the landscape be both instructive about ecological processes, but also informative to the students about where they are on the planet?

To me, voicing those questions was very powerful.

And it was a reminder, looking back on it, of how challenging it is to actually meet those objectives. We had WM+P’s sister company, MBDC, on our side, and access to some incredible indoor air quality experts, but it was hard to try to assess every material selection on the project, and every specification, when there just wasn’t deep research on much of anything. There were no product lists we could go to to meet those specifications. It was a steep learning curve.

AB:

In the era of LEED and Living Building Challenge and the codification of sustainability in architecture, how does it feel to look back on the Oberlin building as a progenitor of that?

KB:

I think David saw the building as a stepping stone, and it was interesting working with him closely throughout that whole process, because he was a great leader. He both saw the critical importance of getting the building right, but he always had a view beyond it at the same time. It was a unique quality, I think, to be in the midst of something that intense and be able to step back and see the long game.

What he realized, I think, was that if they get this building built, it will become a seed crystal. It will be an attractor for students and faculty, it will put the college on the map and maintain the progressive legacy that Oberlin’s had throughout the years. It was the next step in that lineage.

But he had a vision of a campus-wide sustainability initiative back in 1998, which they were calling the 2020 Initiative—which is ironic, being now past 2020—where they were looking at carbon emissions and getting a zero-carbon campus. What would it take to achieve that, having just gotten to a net-zero, net-positive building?

Also what was special with David and his view of sustainability was that the vision didn’t stop at the confines of the campus. Oberlin is such a great example of the small liberal arts college in a small town, and the melding of campus and community.

It has quite a beautiful layout of a central green, with the college on three sides of it and the town on the fourth side. But the town was facing a lot of economic hardship. So David saw this initiative of sustainability operating at the scale of the college, the town, and the region, and integrating all of those together. He would use the building project as a means of engaging city leadership and community residents in the nature of the project, and expanding the aspirations of the project to become more of a regional initiative.

A number of the recent graduates from David’s program became restauranteurs in town and established restaurants based on local [food] production; they became developers and developed LEED-certified buildings downtown and helped revitalize the downtown; they started a farm that Oberlin owned that was growing local food and was supportive of food production in the community; they started to influence the curriculum in local schools.

So I think the seed crystal quality of the project, and the nested scales of ambition that it was able to address, is still unique and is a great model, even in this era. So many projects have looked to build upon Oberlin and exceed its achievements, which is the whole point.

AB:

I want to hear a little bit more broadly about how codified sustainability has become in the realm of architecture. What are the opportunities and limitations?

KB:

That’s a good question. So the Gap was from ‘94, built in ‘97; Oberlin started in ‘96 and took until 2000 to finally be built. The US Green Building Council was emerging in the late ‘90s and the first USGBC conferences were happening in 2001, and LEED 1.0 was right around then. The Committee on the Environment—the AIA’s group—was forming in the early ‘90s and was just starting to hit stride in the early 2000s. So I think the entire movement started to come to light in the late ‘90s. Architectural practices and even owners were starting to take stock of the movement in the early 2000s.

LEED was really critical to the rapid growth of the movement, I think, because it gave a framework that design teams and engineers could all refer to. But just as importantly, it was for owners and builders to have a checklist, and a reference point for what success might look like.

To LEED’s credit, they continued to evolve the certification and the standards to incorporate new input. I think the evolution of LEED over time has been positive, in that it has increasingly taken into account local conditions, local markets, and health and well-being. All of those things are positive.

I remember going to some of the US Green Building conferences in that era where people were also trying to crack the code on the economics of green buildings. Major developers like Hines were seeing the corporate interest and the ‘good design is good business’ side of things, but they were trying to get the economics down, especially when you were incorporating so many new systems that hadn’t been incorporated in buildings at scale before.

It was a reminder of how extremely challenging buildings are in the first place. And then throw on top of that this high bar agenda that has to succeed on environmental issues, health issues, economic issues, and the equity and social component of sustainability as well.

Even looking back on this 25-year, 30-year arc and the great successes and the incredible work people have done, we’re still in very early days in terms of really, as a culture, achieving sustainability. It’s still kind of this goal to pursue.

And the greatest challenge now is the realization that we just don’t have that much time, with the imperatives around climate change and carbon. It’s almost like the realities are kind of coming into focus as our skill-set is emerging, and I think it’s a real question whether we’re going to be able to get there in time.

AB:

Can you talk about the experience of working with Bill McDonough in particular? How was the culture of his office distinct?

KB:

I feel fortunate to have had the chance to work so closely with Bill over the course of 16 years, at a time when the movement was so emergent and he was playing such a pivotal role in that.

What stands out in my memories of William McDonough + Partners is that there was always a need to do what architects do within practice—all of the opportunities and challenges that come along with just doing projects—but there was always something more that was associated with what Bill was doing and trying to achieve in the world. So we had to navigate both realms concurrently.

We had great opportunities with companies like the Gap, or Ford, or Aspect Communications, VMWare, or communities, cities, or regions that would be interested in the way of thinking. There was always the design task at hand, but we were also trying to forward a movement, whether that was Cradle to Cradle or sustainability writ large. And that could be, at times, quite frustrating and quite challenging, but it was what kept it exciting and a unique way of thinking about the role of design.

AB:

You mentioned communities—one of the other projects I wanted to ask you about was the Fuller Chapel, which was one of the other projects you designed while at McDonough’s.

From what you’ve told me, that space was designed to serve a lot of different functions for different communities, and feels like a very community-informed design. What was your experience with that?

KB:

Fuller, in some ways, is emblematic of the type of projects we would get at McDonough’s, and the levels of engagement that would come with that. We got the project initially because one of the board members at Fuller, William Brehm, had come across Bill in their mutual work with Herman Miller. He was taken by Bill’s thinking and approach to sustainability and its potential to impact the entire Fuller community—which is one of the largest, if not the largest, interdenominational theological seminaries in the country.

We were involved for many years, first doing master planning for the campus and then getting the opportunity to design a worship center for them, as well as an addition to their library. It was emblematic of what the seminary was about, which was the head and the heart: the potential for deep research, but also worship.

The unique thing about Fuller is that, although they had been a seminary for 50 or 60 years, they had never had their own place of worship. This became the opportunity to give physical embodiment to this rich, diverse, and creative community. That’s what the worship center needed to embody.

A lot of the worship that happens at Fuller is through performing arts. So in a lot of ways, designing the worship center was like designing a performing arts center. Bill Brehm, in addition to being head of a couple different companies and a philanthropist, is also a composer. So he had a strong desire to see the performance aspects be carried out at the highest level of excellence, and that’s what the design gave us the opportunity to explore and to implement on the campus.

AB:

What elements of that design feel most successful to you, not just in accomplishing what it needed to purpose-wise—and I know there were a lot of complex considerations of different performance configurations and different acoustics—but also on a more ethereal level?

KB:

Unfortunately the worship center has never been built. They did build the addition to the library, but I still have my fingers crossed that someday they will build this. That said, the design was very well-received by the community.

I remember sitting through visioning sessions with the various faculty members and one of the faculty members said, ‘I think this building needs to be a building that can house our dreams as a community.’

There’s something about the way she expressed that—both the poetics of that and the nature of that ambition—that stayed in the back of my mind during the design. This needed to be more than, as you noted, just a lot of high performance around acoustics or flexibility or daylighting.

I do think the design was able to capture a type of spirit in the quality of light and the variable acoustics. They wanted a space that could feel intimate if a single person went in looking for a place of solitude or prayer; if two people were there; if a small quartet were there performing; if it was more of a music group—be it rock music, a capella, or an orchestra. It needed to have a variable acoustic that would make all of those achieve a level of transcendence. And I think the design was able to achieve that.

AB:

Was that one of the first projects where you were dealing with acoustics more centrally, or has that always been a consideration?

KB:

We had addressed acoustics more broadly in corporate office buildings, which was about creating absorption in the space through acoustic metal deck or those types of considerations, or dealing with the sound of an adjacent road or something like that. So it had definitely played a part in thinking about holistic, experiential design, but this was the chance to take it to another level.

We worked with theatrical consultants on how to achieve a variable acoustic, which we developed behind these wooden slat walls that had an absorptive fabric behind them that you could lift or settle depending on how much absorption you wanted the room to have—either to create a very lively, bouncy space or a very absorbent space. You could set that both in the walls and in other acoustic material that could be pulled above a suspended skrim in the ceiling. There was an ability to modulate the reflectivity or absorption of the space that was something more akin to what you would see in an auditorium or performance hall.

AB:

I feel like that high level of consideration in variability of experience feels emblematic of a lot of the other work you’ve gone on to do—your building for Google at 1212 Bordeaux has that quality.

Back to what you had said about the Gap, with the operable windows being against conventional wisdom, the idea of experiential variability feels like a throughway in how you think about design.

KB:

Definitely. In some ways that’s a quality that is part of every project we’ve done, regardless of scale. And actually, in terms of instilling a response—of people feeling really connected to a place—giving options is almost like designing for a cat: you want to create places of thermal variability or light variability that just give people choices.

Prior to this kind of thinking about design, architects had always assumed that a house would give you that kind of choice, whereas an office building had, in the modernist language, been designed to create sameness: the same levels of light, same temperature, same acoustics.

I think a lot of what emerged was from work that Google had done early on, thinking about the office and creating variability as part of it, both inside and outside, and thinking about how the landscape could become part of the office experience. It’s definitely something we have looked to further in all of our projects.

A CONVERSATION WITH CARRIE MEINBERG BURKE

Design The Future podcast

PARABOLA Architecture principal Carrie Meinberg Burke was a recent guest on the Design The Future podcast, where she talked with hosts Kira Gould and Lindsay Baker about her design philosophy, career trajectory, and thoughts on the future of the sustainable design movement.

You can listen to the podcast here, and a full transcript of the interview is available below.

KIRA GOULD:

I’m so excited about our guest today, we have Carrie Meinberg Burke with us today. Welcome, Carrie.

CARRIE MEINBERG BURKE:

Hello!

KG:

We’re so glad you could join us today. I’m going to start with a little introduction of Carrie—Carrie is an architect, an artist, a designer, and an inventor whose work operates at the nexus of art and science. Honed through decades of experience, her analysis/synthesis design methodology has been applied to challenging design problems to uncover unique forms of intrinsic performance and enduring beauty. Her work is infused with research into light, ecology, health, human-sensory perception and biomimicry.

After practicing on her own, she launched PARABOLA Architecture with Kevin Burke in 2011. PARABOLA’s built projects include 1212 Bordeaux, Google’s first completed ground-up building and prototype for their future workplaces. Carrie is also co-developing an innovative heating and cooling unit that applies biomimicry principles to optimize form for thermal comfort and energy efficiency, and she’s going to tell us more about that.

But first, Carrie, I wonder if we could start off—if you could tell us a little bit about how you got interested in architecture and sustainability. Really, what has been your path?

CMB:

Thanks for having me, and asking these very provocative questions. It’s been great to reflect back on how I really got here for this podcast, and I think it’s really useful for all of us to do that now and then. It starts, of course, for me, with very supportive parents. They always supported my creativity and encouraged me, and there’s probably some significance to the fact that my mom is very much an intuitive creative person and my dad is a very methodical budget analyst. So I definitely come with a type of mind that I found was very fitting to architecture.

Growing up we lived overseas for a couple of years, so in the absence of media I used to keep myself occupied by doing things like growing salt crystals—I would super-saturate some salt water and I would get out the magnifying glass, and every day go and watch these crystals forming. And I’m bringing this up because I can see this as a type of observational curiosity that I had as a very young child, sort of seeing an order in nature and a sort of order in randomness that appears from that kind of study.

You can listen to the podcast here, and a full transcript of the interview is available below.

KIRA GOULD:

I’m so excited about our guest today, we have Carrie Meinberg Burke with us today. Welcome, Carrie.

CARRIE MEINBERG BURKE:

Hello!

KG:

We’re so glad you could join us today. I’m going to start with a little introduction of Carrie—Carrie is an architect, an artist, a designer, and an inventor whose work operates at the nexus of art and science. Honed through decades of experience, her analysis/synthesis design methodology has been applied to challenging design problems to uncover unique forms of intrinsic performance and enduring beauty. Her work is infused with research into light, ecology, health, human-sensory perception and biomimicry.

After practicing on her own, she launched PARABOLA Architecture with Kevin Burke in 2011. PARABOLA’s built projects include 1212 Bordeaux, Google’s first completed ground-up building and prototype for their future workplaces. Carrie is also co-developing an innovative heating and cooling unit that applies biomimicry principles to optimize form for thermal comfort and energy efficiency, and she’s going to tell us more about that.

But first, Carrie, I wonder if we could start off—if you could tell us a little bit about how you got interested in architecture and sustainability. Really, what has been your path?

CMB:

Thanks for having me, and asking these very provocative questions. It’s been great to reflect back on how I really got here for this podcast, and I think it’s really useful for all of us to do that now and then. It starts, of course, for me, with very supportive parents. They always supported my creativity and encouraged me, and there’s probably some significance to the fact that my mom is very much an intuitive creative person and my dad is a very methodical budget analyst. So I definitely come with a type of mind that I found was very fitting to architecture.

Growing up we lived overseas for a couple of years, so in the absence of media I used to keep myself occupied by doing things like growing salt crystals—I would super-saturate some salt water and I would get out the magnifying glass, and every day go and watch these crystals forming. And I’m bringing this up because I can see this as a type of observational curiosity that I had as a very young child, sort of seeing an order in nature and a sort of order in randomness that appears from that kind of study.

1. Stills from Persistence of Vision film by Carrie Meinberg Burke (1981)

1. Stills from Persistence of Vision film by Carrie Meinberg Burke (1981)I also used to make dolls and cars and just build things, but the doll part was really specific for me, because I was designing joints for the dolls and I would create joints out of pieces of wire. And there was always this part of me that has joined the idea of humans and human nature with the making of things. These dolls were something that were very anthropomorphic for me, both in terms of the structure of the body—which has always remained an interest for me, with health and well-being—but also a kind of analogue to how I understood structure as an architect.

Also, [there is] the idea of infusing a type of user personality in this process when I was little that I do find very relevant to imagining people who might occupy the buildings I’m designing. And that certainly has come more into play as the world focuses more on user experience, particularly through the internet, which has really brought forth that.

But architecture is really something that has that physicality built into it, the human scale built into it, and I just realized in my background that I really wanted to design the experience more so than the object. I almost went into film at a certain point after undergraduate school. Then I realized that maybe I could develop a design method that was more akin to filmmaking, where I would design the experience first, and then the artifact around that that would shape the experience.1

So I decided to go to grad school—this is after practicing for eight years and getting licensed—so I went into the post-professional program at Yale, which enabled me to bypass the technical requirements of the program, since I was already licensed, and really take anything I wanted from the college.

Also, [there is] the idea of infusing a type of user personality in this process when I was little that I do find very relevant to imagining people who might occupy the buildings I’m designing. And that certainly has come more into play as the world focuses more on user experience, particularly through the internet, which has really brought forth that.

But architecture is really something that has that physicality built into it, the human scale built into it, and I just realized in my background that I really wanted to design the experience more so than the object. I almost went into film at a certain point after undergraduate school. Then I realized that maybe I could develop a design method that was more akin to filmmaking, where I would design the experience first, and then the artifact around that that would shape the experience.1

So I decided to go to grad school—this is after practicing for eight years and getting licensed—so I went into the post-professional program at Yale, which enabled me to bypass the technical requirements of the program, since I was already licensed, and really take anything I wanted from the college.

2. From theory to practice: Timepiece is a built exploration of Meinberg Burke’s theoretical work at Yale.

I found that it was really a time for me to uncover the black holes in my education, and to fill those in with things I hadn’t learned when I went right into architecture school in undergraduate school. So I ended up very focused on finding ways to deepen my design method and support it with coursework that would help to expand my thinking. I took courses like ‘Infinity and Perspective’ in the philosophy department. I took a seminar where we actually read Vetruvius and Alberti—the original texts—and had a lot of great seminar conversations about that.

At the same time, I was taking a course with Mario Gandelsonas that I expanded into three independent studios with him. And in part it was because I felt that the four semester structure would be a constant process of re-starting new each time. Again, grad school for me was a process of expanding and deepening my understanding, so I really wanted to push through walls that always come up in creativity, and find tools for breaking through those.

Those three semesters were focused on the work that eventually became our house and the studio for PARABOLA, which we’ve called Timepiece.2 And that work was really uncovering a way to shape form with light, and to shape the experience of architecture through more of an understanding of human perception.

In that process, I also developed a tool which I still use to this day, which is a process I call building little thought experiments.3 It’s something I do sometimes to explore an architectural idea without being burdened by needing to be architecture or a building. It might isolate a particular question or thought about architecture. I’m also using it to create some bench test experiments that will inform the convective unit Kira had mentioned that I’m working on with an engineer colleague that I’ll get to in a few minutes.

At the same time, I was taking a course with Mario Gandelsonas that I expanded into three independent studios with him. And in part it was because I felt that the four semester structure would be a constant process of re-starting new each time. Again, grad school for me was a process of expanding and deepening my understanding, so I really wanted to push through walls that always come up in creativity, and find tools for breaking through those.

Those three semesters were focused on the work that eventually became our house and the studio for PARABOLA, which we’ve called Timepiece.2 And that work was really uncovering a way to shape form with light, and to shape the experience of architecture through more of an understanding of human perception.

In that process, I also developed a tool which I still use to this day, which is a process I call building little thought experiments.3 It’s something I do sometimes to explore an architectural idea without being burdened by needing to be architecture or a building. It might isolate a particular question or thought about architecture. I’m also using it to create some bench test experiments that will inform the convective unit Kira had mentioned that I’m working on with an engineer colleague that I’ll get to in a few minutes.

3. Thought experiment: Anamorphic Alberti Box (1991) "...in that a row of columns is nothing other than a wall that has been pierced in several places by openings.

3. Thought experiment: Anamorphic Alberti Box (1991) "...in that a row of columns is nothing other than a wall that has been pierced in several places by openings.

The other exposure to architecture and sustainability that was very important was that my husband and partner, Kevin Burke, was Bill McDonough’s partner for a number of years, so his parallel path working deeply with Cradle to Cradle and uncovering some of the very early solutions to sustainability—and uncovering questions—was happening concurrently with the work I was doing on our house, Timepiece.

As it turns out, Oberlin—the Oberlin building [McDonough + Partners] designed, that Lindsay actually studied in, was concurrent with the design and construction of our house. All of that was pre-LEED, there were really very few guidelines for how to achieve this important work.

Lindsay Baker:

I have to say, it’s cool to hear the mention of Oberlin, it reminds me of when I first met you both. It just feels like such an experience, and you in particular I feel have lived so many lives in that time.

So this is a hard question that I want to ask you, because your work is pretty unique, but can you talk a little bit about people going into the field of architecture—what you think they should be good at or interested in? And maybe, if people are interested in particularly the path that you followed, what tips would you have or what guidance might you have?

CMB:

Yes, that’s a great question. I did teach a semester with Kevin at Berkeley—which is another time that I got to know you—and I think in that process it really did help to solidify the way I feel about what it takes to prepare for this profession. One thing I’ll say is that I know that mine is a very unconventional, non-linear path, and that’s really by design. I have always felt that I needed some balance between introspective, quiet, focused work on my own and collaborative work with others, or working in obscurity at times, without scrutiny, and just developing an idea. And then, when it’s ready to hit air, feeling like that’s when I could really share it.

So I think that as people prepare for this profession, somehow maintaining connection to why it is you choose to be in the profession you’re in—like, what in your heart is really driving you to that interest—maintaining that and cultivating that work in parallel with what you’re learning with others in collaboration. I think it’s really important—and it’s played out in my work over time, how important this is—to uncover design principles that drive the design decisions. That design is so much about decision-making, and the clarity in that process often comes from having some sort of touchstone you can go back to to evaluate whether the design is on track, and if it’s really optimizing for the issues or kind of conundrums that it’s being asked to solve for.

As it turns out, Oberlin—the Oberlin building [McDonough + Partners] designed, that Lindsay actually studied in, was concurrent with the design and construction of our house. All of that was pre-LEED, there were really very few guidelines for how to achieve this important work.

Lindsay Baker:

I have to say, it’s cool to hear the mention of Oberlin, it reminds me of when I first met you both. It just feels like such an experience, and you in particular I feel have lived so many lives in that time.

So this is a hard question that I want to ask you, because your work is pretty unique, but can you talk a little bit about people going into the field of architecture—what you think they should be good at or interested in? And maybe, if people are interested in particularly the path that you followed, what tips would you have or what guidance might you have?

CMB:

Yes, that’s a great question. I did teach a semester with Kevin at Berkeley—which is another time that I got to know you—and I think in that process it really did help to solidify the way I feel about what it takes to prepare for this profession. One thing I’ll say is that I know that mine is a very unconventional, non-linear path, and that’s really by design. I have always felt that I needed some balance between introspective, quiet, focused work on my own and collaborative work with others, or working in obscurity at times, without scrutiny, and just developing an idea. And then, when it’s ready to hit air, feeling like that’s when I could really share it.

So I think that as people prepare for this profession, somehow maintaining connection to why it is you choose to be in the profession you’re in—like, what in your heart is really driving you to that interest—maintaining that and cultivating that work in parallel with what you’re learning with others in collaboration. I think it’s really important—and it’s played out in my work over time, how important this is—to uncover design principles that drive the design decisions. That design is so much about decision-making, and the clarity in that process often comes from having some sort of touchstone you can go back to to evaluate whether the design is on track, and if it’s really optimizing for the issues or kind of conundrums that it’s being asked to solve for.

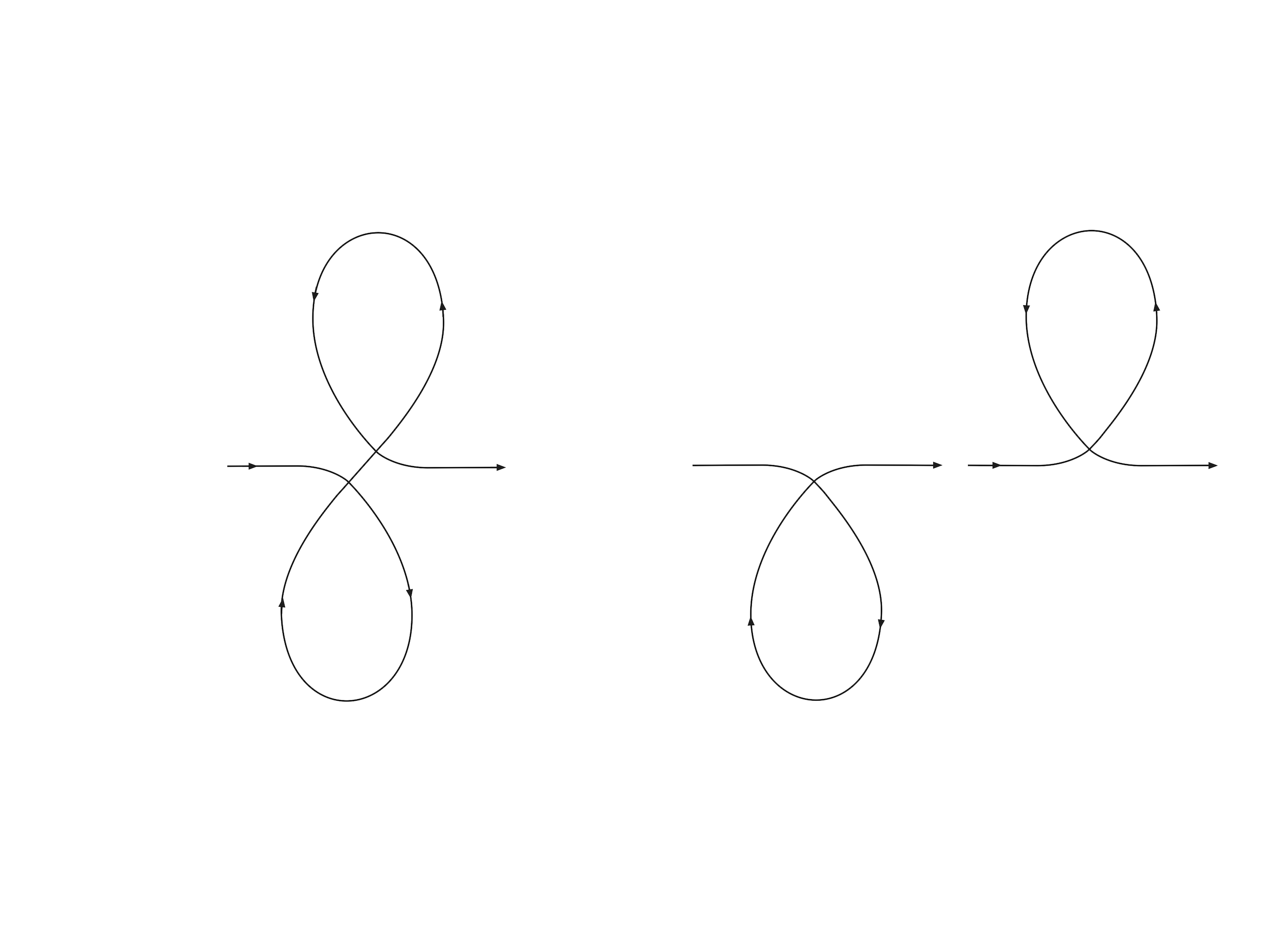

5. PARABOLA’s design process (left) creates resonance between analysis and synthesis, in contrast to conventional processes that separate the two (right).

The other thing that I’ll say—and I learned this from Mario Gandelsonas when I was in grad school—he described the importance of switching gears between analysis and synthesis.5 His point was that you need to create a resonance in that that is so rapid it’s almost like a tone—so at some point you don’t even feel yourself switching gears as much. You’re just basically analyzing, and then making something, which then raises new questions, which you then analyze further, which then gives you more input—and you go back and forth.

That’s in comparison with something that you might consider a rush to form, which is to take all this information and make something quickly from it without building this resonance back and forth. And I’ve seen this in situations where I’ve been teaching or on a review, where I will see that a student has just spent most of their time analyzing, and then whatever form they present after that really has very little input from the analytical work they’ve done.

KG:

That’s so cool. I’m just reflecting on how the way that you think about your work—the way that you got to take a break from practice and go back to Yale and take classes in all these fascinating things, I’m like, ‘Wow, this is what that can lead to.’ I feel like there’s also something there about what it means to go back and think about process and think about theory.

So with that, we want to start talking a little bit more about the products, I guess, of your work, and wondering if you can tell us about some of the most meaningful accomplishments in your work life so far.

CMB:

Yes, and that’s always the hard part, the narrowing down. But what you just said is so relevant because so much of what is most meaningful to me has been this ability to resonate not just between analysis and synthesis, but between theory and practice.

The method I was working on in grad school really did give me a launch point for how to rethink the way I was designing. But it didn’t, at that point, give me the tools to manifest that in built form. And so that’s where some of the projects—the actual built artifacts that came out of that—are the things that really did enable me to deepen that method, and to also create much more continuity with the theory. So it really created a way for me to have the opportunity to be in design leadership roles. In part, I feel like it gave me not only tools, but a type of confidence in the type of design process I was working with. And also it enabled me to be able to collaborate better with other professionals.

That’s one of the things that has been my main transition from design leadership as a sole practitioner to launching PARABOLA with Kevin, the way we’ve had the opportunity to both keep our individual approaches to design and actually create much more of what we consider ‘binocular vision.’ We don’t blend our work or compromise in the conventional sense, but we really came to this with our own backgrounds to bring to PARABOLA a type of design process that would allow us to manifest the process into an architecture that we feel is very fitting to, again, the conundrums it’s being asked to solve for. We often get really great challenges from our clients, who really want to resolve or solve very ambitious problems. It’s helped us to design with engineers and builders, bringing them to the table at the beginning instead of as an afterthought.

That’s in comparison with something that you might consider a rush to form, which is to take all this information and make something quickly from it without building this resonance back and forth. And I’ve seen this in situations where I’ve been teaching or on a review, where I will see that a student has just spent most of their time analyzing, and then whatever form they present after that really has very little input from the analytical work they’ve done.

KG:

That’s so cool. I’m just reflecting on how the way that you think about your work—the way that you got to take a break from practice and go back to Yale and take classes in all these fascinating things, I’m like, ‘Wow, this is what that can lead to.’ I feel like there’s also something there about what it means to go back and think about process and think about theory.

So with that, we want to start talking a little bit more about the products, I guess, of your work, and wondering if you can tell us about some of the most meaningful accomplishments in your work life so far.

CMB:

Yes, and that’s always the hard part, the narrowing down. But what you just said is so relevant because so much of what is most meaningful to me has been this ability to resonate not just between analysis and synthesis, but between theory and practice.

The method I was working on in grad school really did give me a launch point for how to rethink the way I was designing. But it didn’t, at that point, give me the tools to manifest that in built form. And so that’s where some of the projects—the actual built artifacts that came out of that—are the things that really did enable me to deepen that method, and to also create much more continuity with the theory. So it really created a way for me to have the opportunity to be in design leadership roles. In part, I feel like it gave me not only tools, but a type of confidence in the type of design process I was working with. And also it enabled me to be able to collaborate better with other professionals.